City of Women - Stadt der Frauen The female perspective on Viennese Modernism

- Mar 26, 2019

- 5 min read

This article recently appeared in print in issue no 6 of ArtPaper Malta.

If it were just a question of surnames, I am sure that Klien and Steiner would be up there with Klimt and Schiele as names we associate with Viennese Modernism. It is when you look at the first names that you realise why they aren’t. Klien and Steiner were women. They were well known in their time, exhibited with their male colleagues and contributed significantly to the achievements of Viennese Modernism. Yet, they were largely ignored later on, once art history was given importance again at the end of the Second World War.

There are several reasons why these women do not appear in the annals of art history. Many of them were Jewish and with the Anschluss of 1938 they, and their art vanished from public view. Most of them migrated, several were being deported and sadly, some, like Friedl Dicker Brandeis and Helene von Taussig, died in concentration camps. Their presence on the artistic scene, which was so hard-won, faded. Eventually they completely disappeared from public consciousness. Once the war was over, art historians found it simpler to concentrate on the male names of Vienna’s Modernism, wiping out the artistic emancipation of these women.

It is remarkable that in a large-scale art show (presided over by Gustav Klimt) in 1908, over 30% of a total of 179 artists were women; whereas in 1986, Kirk Varndoe, the then curator of MoMA in New York, went so far as to exclude all female artists when he put on the show Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture and Design. His viewpoint was that modern art ‘began largely as an endeavour of white European males’ and to put it bluntly, he found that no female artist’s work was worthy to be hung on the walls of his museum.

Seeing that Klimt and his fellow Secessionists were so welcoming of their female colleagues, it is a shame that City of Women could not run concurrently with the major retrospectives that were put on in Vienna in 2018 to celebrate the centenaries of the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, amongst others. But to quote the exhibition’s curator, Sabine Fellner, “sometimes it’s difficult to coordinate these things”.

When I went to see this exhibition, spread through the splendid rooms of the Lower Belvedere Museum in Vienna, I was lucky enough to catch part of a guided tour with Fellner. It is due to her passion and meticulous efforts that this showcase of 56 female artists saw the light of day. She tells stories of having to search the archives of the museum and track works through gallerists and descendants of the artists. She finally put together this show that spans a period of close to 40 years and several movements, from Atmospheric Impressionism and Secessionism to Expressionism, Kinetism, and New Objectivity.

Fellner spoke of how one iconic painting by Broncia Koller-Pinell called Early Market that was thought to have been lost, was found hanging unnoticed in a provincial school in Lower Austria. Now, this very Broncia Koller-Pinell had gained international recognition in the exhibition of 1908, when an art critic of the time said of her that “..there is a true energy, not imitative of the male, in this artist’s brushstroke and framing of forms”. She was a respected member of Austria’s artistic elite in her time, forming part of the circle around Klimt. And yet, ironically enough, as recently as 1980, Austrian media branded her a “painting housewife” on the occasion of a major retrospective of her work.

Still, there is nothing housewife-like about these works of art. The artists display idiosyncratic styles and also impress with their versatility. Alongside paintings and sculptures the exhibition comprises delicate watercolours, detailed ink and pencil drawings, multi-coloured woodcuts as well as exquisite etchings and lithographs. There are also a few bold and expressive enamel paintings and two examples of faience maquettes. The latter, two ceramic bas-reliefs by Elena Luksch-Makowsky, were the models for a dynamic architectural relief that used to grace the facade of the Buergertheater in Vienna until the building was demolished in 1960.

Another documented commission is the work of Eugenie Breithut-Munk, who painted allegorical murals at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna that to this day adorn the walls of the building. Breithut-Munk was a member of the very active group Eight Women Artists that served as a platform for female artists at the time. The group held successful exhibitions in one of fin-de-siècle Vienna’s most important galleries. This led to national collections taking an interest and acquiring the works of these artists.

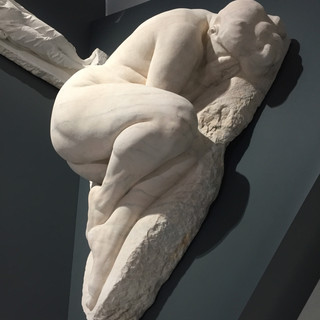

Another one of the founding ‘eight’ artists was the Russian born Jewish sculptor and painter Teresa Feodorowna-Ries, who was working in Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century. In fact, it is her remarkable sculpture titled Witch doing her Toilette on Walpurgis Night that greets the visitor on entering the exhibition space. Unsurprisingly, this white marble sculpture, which shows a nude woman cutting her toe nails, caused a scandal when it was first exhibited in 1896. Yet despite - or possibly because of - her provocative work, Feodorowna-Ries became a successful artist.

Tina Blau, a landscapist, was another success story. She was a co-founder and teacher at Vienna’s first art academy for women and contributed considerably to the development of a style of Austrian landscape painting called ‘Atmospheric Impressionism”. Curiously, one of her key works, Spring in the Prater, was initially rejected by the organisers of an international event at the Kuenstlerhaus exhibition centre in 1882 for ‘excessive brightness’; yet, it was later included and eventually acquired by the Imperial Picture Gallery.

Stephanie Hollenstein served in the First World War disguised as a male soldier, and once exposed, ended up as a military painter for the Austro-Hungarian War Office. The exhibition contains her rather striking, yet confusingly-titled Portrait of a (male) Soldier - Self-portrait amongst other expressive and emotive works.

There are the abstract figurative paintings by My Ullman and Elisabeth Karlinsky and Erika Giovanna Klien’s panels in bold colours that pertain to Viennese Kineticism, also dubbed ‘Modernism in motion’. This Avantgarde movement - an amalgamation of expressionism, cubism, futurism and constructivism - was initiated by a man, Franz Cizek, but mainly carried out by women artists.

Margarete Hamerschlag and others produced high-quality woodcuts exploring existential and social subjects, highlighting the misery of life in the cities of the time.

Many other works also clearly show the influences of the era and its history. One particularly poignant example is the haunting painting titled ‘Interrogation II’ by Bauhaus-educated Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. She left us a legacy not only in her oeuvre but also in the art education she gave to Jewish children while teaching them during their (and her) imprisonment in the ‘model ghetto’ Terezin.

The biographies of these women artists do tell us about their achievements, where they exhibited, which associations they founded or belonged to and where they taught. But they often also contain references to who their fathers, brothers or husbands were. While that might be of interest from a purely biographical point of view, I will welcome the day when a woman artist will be defined purely by her work.

City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna from 1900 to 1938 is on show at The Lower Belvedere in Vienna until 19th May.

Material about these women artists is not very easy to find but here are some links if you are interested in their individual biographies:

If you want to read about the male part of Viennese Modernism read my blog post on it here.

To enjoy the pictures and their details better, please click on them, there is also additional information in the captions:

Comments